|

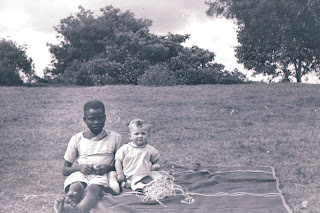

| With Wilson |

I was five years old when the first pains began to twist and turn in my tummy. Earlier that morning, I was playing with my African friend, Wilson. He and I were inseparable, and we went everywhere together every morning and afternoon. Wilson's father was an African evangelist, teaching in the Bible School. We often strolled across the football - soccer - field. It was used every day by the young men who studied with Wilson's father, and by children at the nearby elementary school.

The fresh mound of red-brown dirt at the far end of the sports field marked a new grave. The sight would not leave me. In my mind, I kept walking toward the place where Rosalie was buried a week before. She died before reaching twenty. The word used by my parents, "consumption," either in English or Tugen, meant little to me.

I kept going back to the previous days when I was at Rosalie's bedside

as we sang her favorite songs. The last song she wanted to be sung was "On Christ, the solid

rock I stand." This lovely young African woman had been my best friend. She had been taking care of me since I was a toddler. Every morning, my mother, a nurse, attended to the long line of sick people who lined up early every day at the

medical clinic, so Rosalie watched over me.

Many

people sat around her bed. The scene came back. I knelt beside the African pastor who was on one side,

and my father on the other side. We held hands around Rosalie's bed as she breathed

her last. "My hope is built on nothing less,

than Jesus' blood and righteousness." The words were in Tugen, the language of

the people in Kabartonjo.

The day after she died, shortly after the noon meal, Rosalie's body was lowered into a newly-dug grave. Close by was an enormous shade tree.

Then, only a few days

later, my father held my little hand in his big, steady hand. We walked

acrossWith Rosalie

the sports field and I looked up at him. "Squeeze my hand harder, Daddy."

When he squeezed my hand, I felt secure. "Squeeze harder!" It was

easy, at age five, to feel safe when he held my hand so tightly.

That night I first heard my parents talking about the worrying political situation

in Kenya. They thought I was asleep in bed, but I was still awake, thinking

about how Rosalie had died. One thing wouldn't leave me. When her relatives came for the funeral, more than

fifty members of her family decided to follow Jesus.

Earlier, in the afternoon, I felt safe. My dad's firm grip hand gripped my mine, but the pleasure of that afternoon was spoiled that night. My father explained to my mother his anxiety about the dangerous times ahead. I lay in bed and heard him say, "The chief is against me for my speaking out about the things we object to." As a five-year-old, I didn't know anything about FGM, female genital mutilation.

All I knew was that my mother looked after twenty teenage girls in a girls' school and dormitory. They came from families who didn't want their daughters to go through "customs." This was the other work my mother carried out.

"And outside this area,

quite far away," my father continued, "Mau Mau soldiers are demanding that white settlers leave

Kenya." It was the first time I heard all these strange words, and I

didn't know what they meant, but I knew it meant trouble was ahead. A strange sensation hit me. Pain gripped my stomach.

(This is a passage from a forthcoming autobiography, "Stay On Track: Colony Ending Insights.")